Stop using Git like 2014 Word

“The road to hell is paved with works-in-progress.” — Philip Roth

When I was in middle school, I dreaded working with Word in a team.

The workflow involved making your revisions and emailing the revised file to the group. If you were lucky, you could use the automatic merge feature to combine the document with your own work. If not, you would have to manually combine the documents to preserve the changes in each.

With a bad team, combining work was often slower than rewriting.

Eventually, I swore off manual recombination approach, and started assigning one member of the group exclusivity over the document to work each day, so we could email out the revised document to the team without trying to combine anything.

This worked, but people often wanted extra time not built into the schedule or let their designated day go by without making any changes. The strategy only worked as long as there was never a need to work at the same time. It often crumbled when deadlines approached.

Modern Git == 2014 Word

If you too used Word + email collaboration, you might feel an uncanny resemblance to another collaborative tool we use every day: Git.

Every team has a different Git strategy, but they all abandon it as soon as things get tricky. It seems like no matter what you do, conflicts creep into pull requests. The best defense against conflicts is to always work on completely separate parts of the codebase, but — as with Word — sometimes this isn’t practical.

Google Docs

A few years later, my problems were solved when our school district switched to Google Docs.

Google Docs changed everything. Suddenly, conflicts were a thing of the past, and it was no longer necessary to have a strategy in order to collaborate on documents. Sure, it was possible to accidentally type over each other, but this would be caught in seconds, not at the end of the day or week when we tried to recombine our separate work.

Collaborative document, presentation, and spreadsheet editing is now standard across all office suites, and it’s rare to run into collaborative issues in these contexts.

So why do we still struggle with collaborative in software?

Software collaboration is harder

Why not make Google Docs for code?

Well, Microsoft did. It’s called VSCode Live Share, and it’s a brilliant tool for pair programming.1 However, unlike Google Docs, VSCode Live Share doesn’t scale to entire teams.

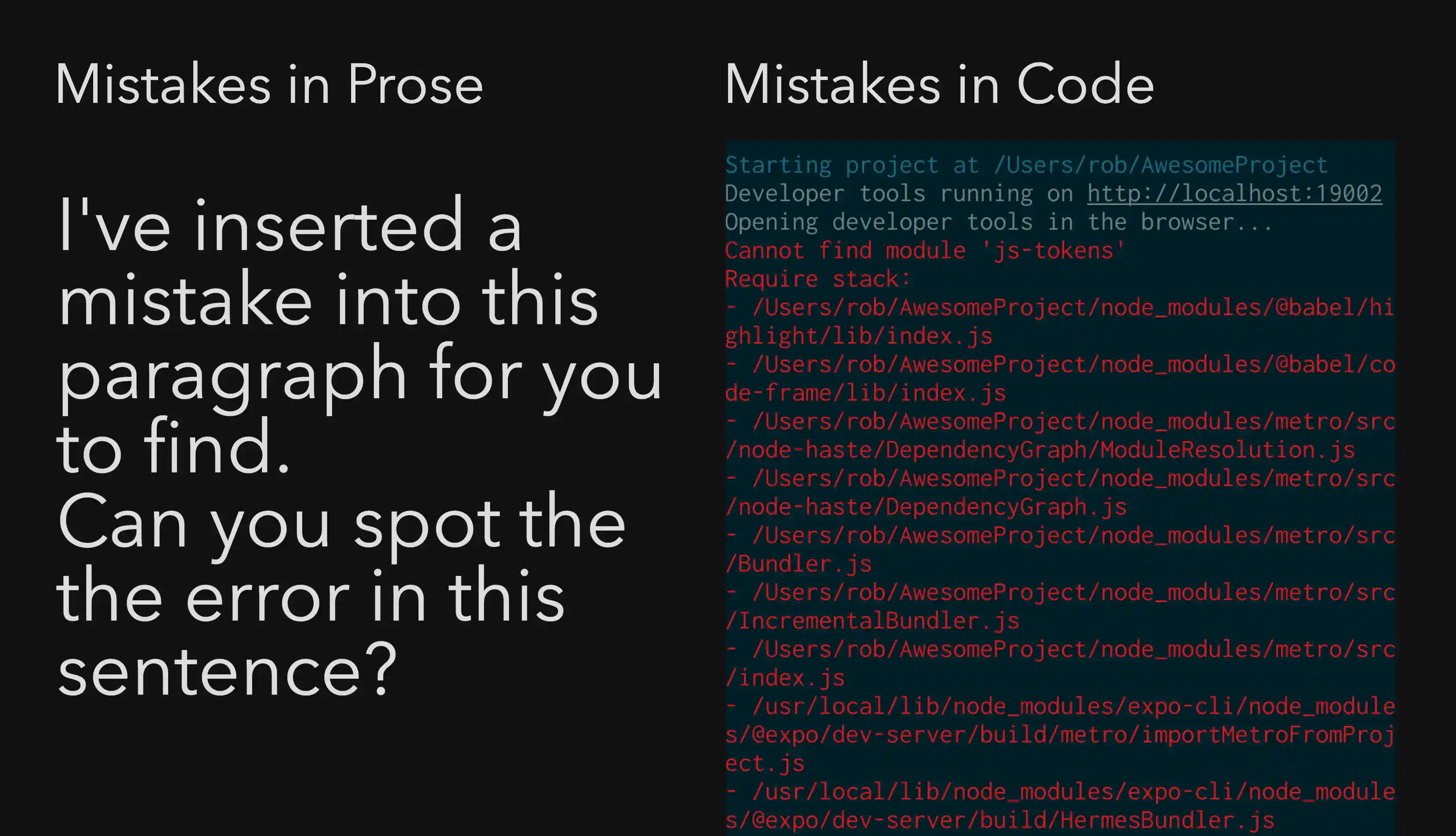

The reason is that partially-written documents are unfinished, but

partially-written code is broken. My coworker’s half-finished page 6 doesn’t

impede my own work, but their half-finished utils.ts will break the build.

If we all wrote code in one giant VSCode Live Share, the experience would be terrible, because you would never be able to build the project, let alone carefully debug subtle bugs in isolation.

However, many people seem to think the only alternative is heavy branching and merges.

The bog-standard approach to Git typically involves 3 steps:

- Branch off the shared development branch.

- Make your changes.

- Create a pull request back into the shared development branch.

I believe there are some reasons why this approach is typical.2

- Merge conflicts are scary, and this approach ensures they can happen at most once, at (3).

- Code review/automated testing is necessary, so a separate branch is needed to hold the changes for review.

These are good reasons — good enough that many people don’t realize this isn’t the only approach. But there is another way, and it has to do with my friend Google Docs.

The Google Docs Workflow

While we can’t plug everyone into one Google Doc for code, what we can do is emulate the process as closely as possible. What is it about Google Docs that enables the seamless collaborative experience?

The key is continuous synchronization between collaborators. Word + email workflows merge daily or weekly; Google Docs merges within seconds. It’s the frequency of teamwide synchronization that prevents merge conflicts from coming up.

When we choose not to merge main until we’re done to “limit merge conflicts”,

we’re just trading frequency of conflicts for severity of conflicts. Cleaning your apartment only once a year

doesn’t make it easier, it just means it will take all week.

Some will argue that long-lived branch workflows cause no problems for them, and it may even be true. When there are no meaningful conflicts, whether you recombine incrementally or merge once at the end doesn’t matter. This doesn’t mean long-lived branches are the way to go, just that you got away with it.

When there are meaningful conflicts, you want to run into them early. Choosing to ignore conflicting commits until you’re done is just sticking your head in the sand until merge time.

Most engineers during the development process.

Conflicts mean that someone else is touching the same code as you. What usually happens is that there’s a race (deliberate or not) to merge first, and then all the merge conflict problems are pushed onto the other person. This pattern is terrible for team productivity as a whole, and often unfairly puts the work of resolving conflicts on certain members of the team.

What you should do when you notice conflicts early is coordinate with your teammate to avoid duplicating work or making incompatible changes. Alternatively, maybe one of you can delay your work until the other is done. Any time you can avoid editing files concurrently, you should.

What does this look like?

So what does this workflow look like in practice?

First of all, it means getting familiar with git rebase. You can get

a similar outcome with frequent git merges, but I favor git rebase. Why?

- Frequent merges pollute the history with largely meaningless merge commits.

git rebaseis a better match to the Google Docs approach.

If you’ve ever used Google Docs on a poor connection, you might know that it isn’t actually perfect. While algorithms guaranteed to deconflict collaborative editing exist, Google Docs uses a more naive algorithm that can lead to conflicts if too much time passes between synchronizations.

Google Docs deals with this by disconnecting clients who have drifted too far and telling them to reload. Synchronization is achieved by making the server state the canonical state, and requiring clients to accept it.

This situation is a perfect mirror of a central Git repository. GitHub’s main

is the correct state, and any conflicts with it are your problem, not the

problem of the central repository.

If you want some intuition for that argument, consider a PR into main that,

when merged, breaks the build. Where does the blame for the breakage lie?

Always with the PR, and never with main!3

git rebase is accepting the upstream as correct, and rebuilding your changes

on top. git merge confusingly maintains both histories as equals, when

generally they are not.

Now, this isn’t to say that git merge is never correct. Sometimes a branch

has been alive for so long that a merge is the pragmatic choice to resolve

conflicts.4 But far too often I see a PR with 20 lines changed and 6 commits, 3 of

which are merges from main. These are the scenarios where git rebase shines.

I also think long-lived branches that warrant git merge should be avoided.

Many engineers need to rethink their approach to large-scale changes in order

to live up to this ideal. Gigantic PRs for gigantic changes should never be the

answer.

But code review!

Code review can be tricky. Few teams want full YOLO as their merge policy, but

code review usually adds a blocker to reincorporating code into the main

branch.5 And shouldn’t we want only the best possible code to be merged?

Google has some good guidance on this point:

“In general, reviewers should favor approving a CL [change list] once it is in a state where it definitely improves the overall code health of the system being worked on, even if the CL isn’t perfect.” — Google Engineering Practices

I am guilty of being a perfectionist on PRs, but they have a point. You never want good work to stagnate in review over relative minutiae. Plus, if the review process for changes is fast, minor issues can easily be fixed after the fact.

A good rule of thumb is that fixing a typo or renaming a poorly named variable should take just hours to be reviewed and merged to the development branch. If making a trivial change takes days or weeks, engineers are pushed toward bundling their changes to limit the impact of the long review process.

More significant changes, like features, shouldn’t take more than a few days to be reviewed. PR authors must take this into account also — PRs must be small enough that their review doesn’t feel onerous.

Conclusion

Effective communication is known to be a key part of collaboration. Commits in version control are a form of communication, though we often don’t think of them this way.

Failing to reintegrate changes across the team regularly is choosing to use

2014 Word when we already have Google Docs. Don’t be like the ostrich - get git rebaseing!

PS: If you’re thinking that this approach seems reasonable, but you’ve never heard of it before, it’s not something I just cooked up. This post describes continuous integration and trunk-based development in simpler terms.

Footnotes

-

I keep VSCode installed on my machine just for this feature, even though I use Neovim for everything else. Sadly, there’s not really a cross-editor service for collaborative editing; all of the existing services are limited to “supported editors”, which are usually a mix of VSCode and Jetbrains products. I actually have a to-do item to take a crack at this, because with the likes of Yjs, the hard CRDT problems are already solved. Someone just needs to host a simple backend, end-to-end encrypt everything, and make an open interface that arbitrary editor plugins can implement. ↩

-

I think a significant amount of the popularity of the “branch-and-merge” workflow is directly attributable to this article (which even discredits itself now). I think the high-quality, colorful diagrams are no small part of this popularity. Software engineers are surprisingly susceptible to marketing. ↩

-

This isn’t to say that there can never be bugs in

main, but a PR that exposes bugs is expected to fix them. ↩ -

Rebasing a branch with significant conflicts is extremely painful and error-prone, so sometimes in these cases it’s best to do a merge. However, typically the need for these merges comes up because the branch has too many changes or because another too-big branch has been merged upstream.

It’s also possible to squash your commits and rebase the squashed commit. This approach retains linear history and makes conflict resolution simpler at the cost of granular history. ↩

-

I will note, however, that in small teams of experienced engineers, YOLO merge policy — or even one branch +

git pull --rebase— is actually quite effective and possibly correct. ↩